Creating Change: SmartICE

Enabling Resiliency in the Face of Climate Change

13 Nov 2025

Words by: Kim Holmes

Bold Studio: Can you tell our readers about SmartICE and the social enterprise model it has developed?

Dr. Wilson: In 2010, SmartICE Monitoring and information Inc. was co-created in partnership with the Nunatsiavut Government, born out of a critical need for sea ice safety information, following an unpredictable ice season around Nain in 2009. SmartICE operates as a non-profit social enterprise – a business model that priorities social, cultural and environmental goals over traditional profit motives.

Rather than channeling earnings to shareholders, SmartICE reinvest its revenue to deepen its impact, ensuring its mission to support Indigenous communities remains front and center.

We work for and with Indigenous communities to co-produce practical solutions for adapting to climate change, particularly as sea and freshwater ice becomes increasingly unreliable for travel. Our organization works with individuals to equip them with the tools, training and technology needed to monitor ice conditions for safer travel but also to build transferable skills that can lead to broader opportunities, even outside of SmartICE. SmartICE is currently active in over 35 Indigenous communities across the Canadian Arctic.

Bold Studio: What is your role with SmartICE?

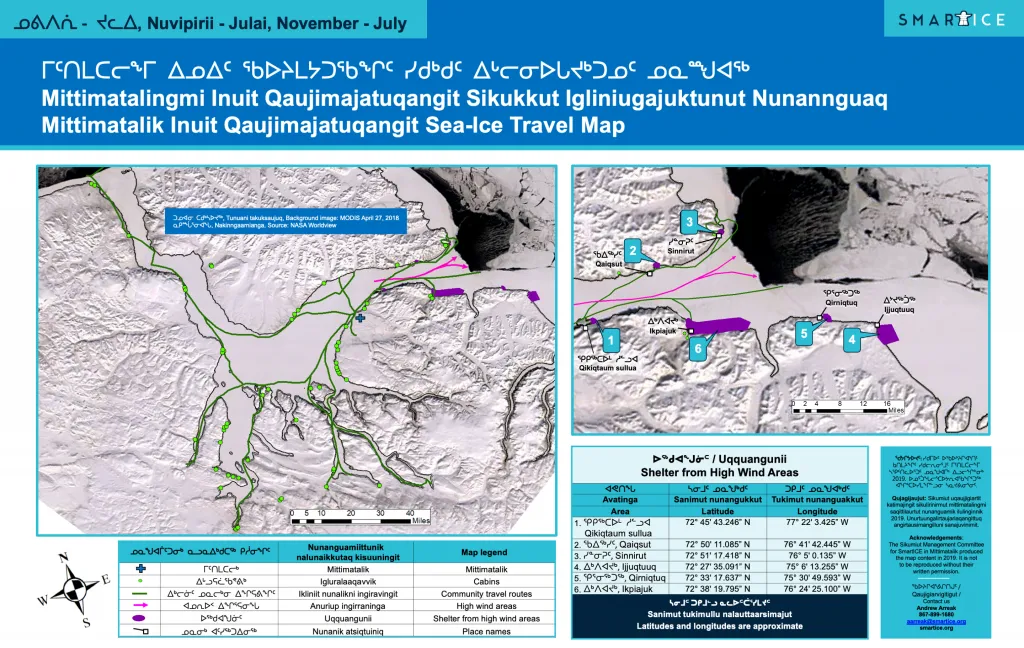

Dr. Wilson: Our program within SmartICE is called, Sikumik Qaujimajjuti (tools to know how the ice is), is dedicated to training and supporting northern communities to monitor ice conditions from above, by interpreting satellite imagery through the lens of Indigenous Knowledge.

Together, we work to document vital local knowledge around ice travel, through creating resources such as maps, posters and terminology books that document local Indigenous travel knowledge to share within the community. This information is then integrated into weekly maps based

on satellite imagery, keeping locals informed about how ice conditions are evolving on a weekly basis.

In my role, I support our network of community knowledge coordinators in 9 communities through a hybrid training model designed to be accessible, culturally relevant, and community based. This approach blends in-person community visits, online meetings, personalized one-on-one support, and biannual workshops held in a northern community. The focus of the workshops is threefold: so our remote learners can meet each other and build relationships; training coordinators in the technical skills needed to use geographic information systems (GIS) and thirdly on interpreting satellite imagery. Leading up to the workshops, during the first few months of the program, we are working on building a strong foundation in digital literacy. Covering everything from using email and Zoom to basic graphic design. Importantly, this training takes place in the North, allowing Inuit to gain skills and employment without having to relocate.

A major component of the program involves supporting the community knowledge coordinators as they document their community’s Indigenous knowledge. This is a collaborative and iterative process, where coordinators form and work with their local community management committees (CMC) to gather insights and develop ice safety products rooted in Indigenous Knowledge. Each training cycle is co-produced with the communities we serve, ensuring the content is tailored to their specific learning needs and delivered in a way that reflects local culture and context.

We continuously refine our training based on feedback from participants and our experiences. Before each workshop, we revisit and adapt our materials to ensure they’re both practical and relevant. After workshops, we continue to meet on a bi-weekly basis as a team and bi-weekly on an individual basis to strengthen and practice the skills learned at the workshops.

Bold Studio: Can you share specific examples of how the integration of Inuit knowledge has improved sea ice travel decision-making for the communities you work with?

Dr Wilson: A key part of our work at SmartICE involves creating tools that preserve and share Indigenous Knowledge (IK) about ice safety—knowledge that has guided communities for generations. One of the most impactful tools that have been co-developed are IK maps, which chart where safe and dangerous travel areas are traditionally found on sea and lake ice surrounding the community.

These maps are grounded in lived experience and observations passed down through generations, offering a local perspective that satellite data alone cannot always capture.

Each week, the community knowledge coordinators enhance their satellite-based ice maps with this layer of local knowledge, ensuring that the maps reflect both what is visible from space and what is known on the ground. For example, certain dangerous areas—like thin ice near currents or ice that's deceptively covered by snow—might not appear in satellite imagery but are well-known to community members. By combining both sources of knowledge, we’re able to provide a completer and more reliable tool for safe travel planning.

Another important resource we’re building are IK Ice Terminology books. These books are cultural archives that preserve Indigenous language and knowledge around ice. They teach people how to recognize different types of ice and understand whether they are safe or dangerous to travel on, placing special emphasis on the terms for hazardous ice conditions. Through this, we not only promote safety, but also help preserve and pass down the language and knowledge systems that have kept communities safe for centuries.

Bold Studio: What challenges have you faced supporting Inuit self-determine in research, and how have you overcome them?

Dr. Wilson: Challenges that we have faced as an organization are related to systemic barriers that can limit access to meaningful employment and training. Specifically, we have challenges with finding dedicated office space for employees, making it difficult for people to have a reliable and quiet environment to work in.

Furthermore, a shortage of accessible childcare options can prevent parents from entering or remaining in their jobs. Despite having the skills and motivation, northern community members have access to fewer opportunities within their communities, as most post-secondary and job training programs are concentrated in the south.

At SmartICE, we work to break down the barriers through our hybrid training approach, which is designed with flexibility and accessibility in mind. Our model allows participants to train and work right in their home communities. We also pay trainees while they learn, ensuring they have financial support and immediate employment. We offer flexible hours and cover daycare costs during any required work trips. By meeting people where they are at, we can create jobs and build sustainable community driven positions to support Inuit self-determination.

Bold Studio: How do you measure the impact of SmartICE initiatives on the local communities, and what indicators of success are most meaningful to you?

Dr. Wilson: At SmartICE, we recognize that evaluation is a core phase of project success—it’s not something we do at the end, but something we build into our work from the beginning. The way we measure impact is grounded in our commitment to community-led approaches. We work closely with rightsholders and stakeholders in each community to collaboratively define what success looks like. These indicators are not one-size-fits-all; they are developed in partnership with community representatives to reflect local priorities, knowledge, and needs.

What’s most meaningful to us are the measures that communities themselves identify as important. While we track quantitative data, our most valued indicators of success are high community satisfaction rates and hearing direct, qualitative feedback that our tools and services have helped people travel more safely on the ice. That kind of impact—knowing our work is being used in ways that support safety and wellbeing—is the clearest sign that we're doing things right.

Ultimately, our impact is rooted in trust, built through meaningful engagement and respectful collaboration. That trust allows us to co-create solutions that are not only technically effective but also culturally and contextually relevant.

Bold Studio: What future projects or collaborations are you most excited about and how do you envision them further benefiting the communities involved?

Dr. Wilson: We are currently exploring how we could gain accreditation for individuals who have completed part of or completed our entire training program. By formalising the program and offering official certification after completion, trainees will have a recognized credential that can help to open doors to future opportunities within and beyond the program.

We are also deeply invested in building our network of local trainees who have completed the three-year program. Our vision is for these graduates to take on leadership roles and eventually deliver the training and mentor others. The peer-to-peer model strengthens long-term sustainability of the program and reinforces the principle of Indigenous self determination.

Equally important as we move forward, we are committed to deepening the relationships in the communities we already work. We will continue to refine and adapt our program and ways of doing things based on the needs of individual communities.

Bold Studio: If SmartICE succeeds in its mission, what does the future look like for the communities you work with?

Dr. Wilson: If SmartICE continues to succeed in its mission, the future for the communities we work with is one rooted in self-determination. In many ways, we are already meeting that mission with Indigenous people documenting critical IK to help with keeping people in their communities safe when out on the land and producing their own weekly ice maps.

However, we are also working towards a future where experienced Indigenous staff take on more and more leadership positions in the organization. Specifically for our program, having trainers from the North travel across the country to deliver the GIS and remote sensing workshops, sharing their expertise and experiences with others; and leading and partnering in research in their communities.

Ultimately, a successful mission not only means safer ice travel but strong relationship building and training to support Indigenous communities to lead the change in climate adaptation and technological innovation, all while staying rooted in their language, knowledge, and way of life.

Bold Studio: Finally, what book of podcast would you recommend to readers?

Dr. Wilson: I recommend,

- Not a podcast but a radio show they can listen to:

https://www.cbc.ca/listen/live-radio/1-89-the-signal/clip/16139143-sea-ice-north - The Meaning of Ice – by Shari Fox Gearhead and others

- Inuit Qaujimajatugangit – What Inuit Have Always Known To Be True by Joe

- Karetak, Frank Tester and Shirley Tagalik

Want to share your creative impact with us?

Get in touch: hello@bold-studio.co.uk